Accessibility Options:

Introduction to the Collection

The Asian art collection at the Lowe includes art of East Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia, ranging from Neolithic works, dated as early as 2,600 BCE, to contemporary examples. Although the works of art in the Asian collection vary in terms of material, technique, and region, they also possess many similarities. While materials and techniques for creating artworks were deeply rooted within local regions, travel along the Silk Road led to the widespread dissemination of these ideas and techniques amongst different cultures. One example of this phenomenon includes the religious traditions of Buddhism and Hinduism represented by religious figures that are recognizable by their established iconography despite variations in their representation across cultures. Additionally, the practice of crafting small sculptures for private devotion was common throughout Asia. Another example includes the highly regarded literati tradition of detailed illustration and calligraphy completed on silk and handmade papers that traveled from China to Korea and Japan. Overall, the Asian art collection at the Lowe offers diverse examples of human creativity that demonstrate both tradition and innovation.

The Silk Road

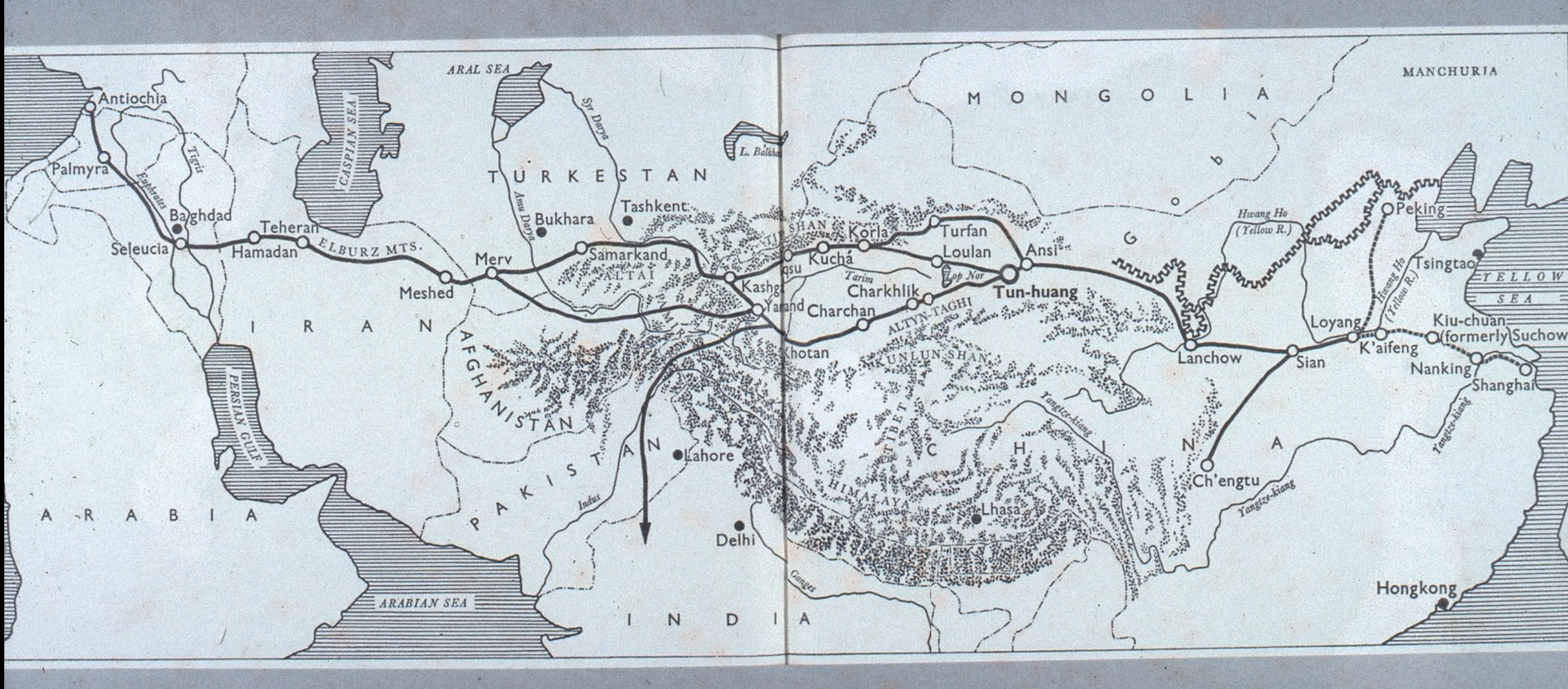

From 130 BCE until 1453 CE, the Silk Road was a network of trade routes that linked the two major civilizations of Rome and China. Silk went westward from China; and wool, gold, and silver went eastward from Rome. The Silk Road was primarily used for commercial trade, but the journey across Asia also provided opportunities for the trade of ideas, religion, and artistic traditions, such as in the transmission of Buddhism from India to China and Japan. In each region, Buddhist figures were created with the local physiognomy, using popular local materials and techniques.

Image of Old Silk Road, ARTstor

Image of Old Silk Road, ARTstor

Gallery

1301 Stanford Drive, Coral Gables, Florida 33124-6310

General Information: 305.284.3535 lowe.miami.edu

Art in Focus: China

CHINA

Ming Dynasty, 1368 – 1644

Guanyin, Goddess of Mercy

Late 16th century

Wood, pigment, and gilding

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Don Solomon, 65.045.361

Guanyin is a Buddhist bodhisattva whose name means “one who hears the cries of the world.” Often known as the Goddess of Mercy, Guanyin is known for kindness, grace, and compassion. In Mahayana Buddhism, Guanyin is considered a potential Buddha in training. In original Indian depictions, Guanyin was a male figure known as Avalokiteshvara, but the figure’s representation gradually shifted to the female image of Guanyin in China. Guanyin’s combination of male and female characteristics led to her status as one of the most beloved Buddhist figures; ancient followers believed she had powers to make miracles happen.

This sculpture exemplifies many of Guanyin’s physical and philosophical characteristics. She is a contemplative figure with downcast eyes and a relaxed face. Like the Buddha, her elongated earlobes suggest that she wore heavy earrings in a former wealthy life. She often wears elaborate robes and a crown on her head, depicting the Amitabha Buddha.

Chinese artists often carved these statues in stone or cast them in bronze but carving sculptures in wood allowed artists to apply color and gilding to the figure. Unfortunately, wood is not as durable as other materials, and this figure’s limbs have broken off, and the pigment and gilding have faded. Originally, her hands likely would have been in the Abhaya mudra—a gesture that represents protection, peace, benevolence, and the dispelling of all fears.

Art in Focus: Japan

JAPAN

Muromachi Period, 1392-1573

Jar (Tsubo) 15th – 17th century

Pottery and glaze (shigaraki ware)

Gift of the Rubin – Ladd Foundation, 2012.9

Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami

This jar (tsubo) is an example of the long history of ceramics in Japan. The Asian gallery at the Lowe currently features a long-term loan of contemporary Japanese ceramics from the collection of Carol and Jeffery Horvitz that connect with the country’s rich ceramic traditions.

The term shigaraki, as exemplified by this jar, refers to a number of kilns scattered over a wide area at the extreme southern part of Japan’s Shiga prefecture. The area has long been known for its clay beds, which have been used by potters since as early as the thirteenth century. The early history of the ware indicates that the kilns were originally operated by a community of farmer-potters, and the pottery produced was confined to local use.

To match its simple functions, shigaraki ware was sometimes decorated with cross-hatched designs, or with a simple glaze derived from the clay of the area, as in the case of this jar. The ware has a high quartz content and the body itself is often embedded with granules of quartz. By the sixteenth century, shigaraki ware had attracted the attention of tea masters, resulting in the production of jars and bowls specifically for the tea ceremony. Tea ceremony aficionados had a deep appreciation of the simplicity, roughness and rustic qualities of shigaraki ware.

Themes in Brief

Religion: Buddhism and Hinduism

Representations: Religious figures and symbols

Secular Art: netsuke; works on paper and silk; sculpture; and ceramics

Themes in Asian Art

Religion is a major theme in Asian art. The Lowe Art Museum holds sculptures that relate primarily to Buddhism and Hinduism, many of which have shared figures, symbols, and meaning.

For instance, Buddhism has figures that are represented in similar ways across time and place. The Buddha has 32 physical attributes that convey his identity. He often sits on a lotus flower; presents a mudra (gesture); features an ushnisha (three-dimensional bun on top of the head to convey enlightenment); has large feet (to represent the Buddha’s long travels); displays elongated earlobes (to draw attention to the Buddha’s former self as an earthly prince who wore heavy earrings); and has an urna in his forehead (symbolizing a third eye that represents vision into the divine world). Buddhist figures differ in description and meaning, depending on their representation and mudras.

Buddhist Bodhisattvas are also represented prominently in the Asian art collection. Unlike the Buddha, who is often humbly dressed in monk’s clothing, Bodhisattvas are shown wearing elaborate adornments that refer to their intercessor roles between the earthly and heavenly realms, as well as their purpose of assisting individuals to achieve enlightenment.

The Asian art collection at the Lowe also includes sculptures that depict figures from Hinduism. One such figure is Shiva, who is the creator and destroyer deity. Shiva is depicted with multiple arms, contained within a circular structure that represents the cycle of creation and destruction. Ganesha is the son of lord Shiva and is shown with an elephant head. During an argument, Shiva cut off Ganesha’s head and then replaced it with the head of an elephant. Ganesha is seen as the remover of obstacles and was often displayed for private devotion. Vishnu is also represented in the Asian art collection. In Hindu religion, Vishnu is one of the primary deities who is known as the Preserver of the Universe.

The lotus flower is represented in sculptures from both Buddhism and Hinduism. Because the beautiful flower blossoms out of the murky water, the lotus flower in Buddhism is a symbol of enlightenment, beauty, purity, rebirth, and spiritual awakening. In Hinduism, the lotus flower has similar associations, as well as being a symbol of spirituality. The lotus flower appears in many sculptures in the Asian gallery.

The Asian art gallery also features many examples of secular artworks—objects not intended for religious purposes. These include ceramic pottery, ceramic figures, sculptures, and works on paper and silk. Included in these secular works are Japanese netsuke, which are small sculptures designed to be worn from the obi (kimono sash) by stringing a cord through a hole in the sculpture. These became popular among Japanese men beginning in the seventeenth century. Many museums have collections of these small, intricately designed netsuke works. The Lowe’s collection includes netsuke made from a variety of materials and designs, as well as tabakoire (tobacco pouches) and inro (medicine boxes).

Regions

Asian art at the Lowe Art Museum comes from countries across East Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia

East Asia

China

Japan

Korea

Vietnam

South and Southeast Asia

India

Indonesia

Nepal

Pakistan

Sumatra

Burma

Tibet

Thailand

Physical Map of Asia

Asian Art Techniques and Materials

Asian art at the Lowe Art Museum includes a wide array of materials and techniques used to produce sculpture and two-dimensional works of art.

Two-dimensional materials

Silk and handmade paper are materials that originate from Asia; artists there have used them for centuries, and they are still treasured today. Although silk is often associated with clothing, it is also used to create Asian screens and scrolls. Because silk is flexible, it can be rolled for easy transport. Rolling also helps prevent fading, which occurs when fabric is left exposed to light.

Asian handmade paper is revered for its strength and chemical stability. Other commercially produced paper can be acidic, but Asian handmade paper often has a neutral pH that promotes preservation.

Both silk and handmade paper are sensitive to light, so the Lowe only exhibits artwork with these materials for about six months at a time.

Two-dimensional techniques

Calligraphy

Chinese brush

Printmaking

Calligraphy, decoratively written script created with brush and ink, is one of the most highly revered art forms in China, Japan, and Korea. Related to the literati tradition, calligraphy is a direct expression of education, cultivation, and beauty.

Chinese brush painting and calligraphy require the same fluidity and mastery of brush and ink, but rather than representing characters as in calligraphy, brush painters traditionally depicted scenes from nature.

Printmaking within the Lowe’s Asian collection is most represented by Japanese woodblock ukioy-e (floating world) prints. These were primarily produced during the Edo period (1603-1868), a time when Japan limited its contact with the outside world. As a result, Edo prints often depict the uniquely Japanese themes of nature (e.g. Mount Fuji), geisha, samurai, and the tea ceremony, amongst others.

Three-dimensional materials and techniques

Materials to cast

Bronze

Copper alloy

Indian artists began casting in bronze nearly 4,700 years ago, and Chinese artists employed the technique over 3,700 years ago. Bronze casting produces stable metal sculptures that are replicable as long as the mold remains durable. Copper alloy is another type of metal used in casting that is comprised of copper mixed with other metals.

Materials to carve

Ivory

Jadeite

Marble

Nephrite

Sandstone

Schist

Soapstone

Stone

Wood

Many of these materials that Asian artists have carved are common in other areas of the world, but a few are specific to Asian regions. Jadeite is a version of jade that is typically pale green in color; it has been found in Burma, China, and Japan, as well as other places around the world. Throughout history, it has been a common material for jewelry and ornamental carvings. In some ancient cultures, jadeite was even more valuable than gold.

Nephrite is considered an older and softer version of Chinese jade but is more common and therefore less expensive. In China, nephrite was known as the Yu stone or the Stone of Heaven.

Materials to fire

Ceramics

Porcelain

Stoneware

Ceramics is the practice of making clay objects that are hardened by heat. The early spread of this art form from China influenced ceramic artists throughout the world, with important traditions of ceramic production also arising in Japan and Korea in particular.

Porcelain is a type of ceramic material that is produced by firing clay at high temperatures, whereas stoneware is produced by firing at lower temperatures.

Techniques for the surface

Gilding

Glaze

Lacquer

Asian artists use several techniques to enhance the surface quality of their objects and sculpture. Artists gild the surface of sculptures with gold leaf to give artworks the appearance of solid gold or add glaze to their ceramic works to create colorful surfaces and decorative motifs. Japanese artists pioneered the use of lacquer to add a dark, glossy surface to their sculptures and utilitarian objects.

Selection of Books

Books

Barbanson, Adrienne. Fables in Ivory: Japanese Netsuke and Their Legends. First ed. Tokyo ;Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle, 1961.

Brinkgreve, Francine., Retno. Sulistianingsih, Museum Nasional, and Museum Volkenkunde. Sumatra: Crossroads of Cultures. Leiden: KITLV Press, 2009.

Brown, Claudia. Great Qing : Painting in China, 1644-1911. China Program Book. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2014

Childs-Johnson, Childs-Johnson, Elizabeth, Taipei Gallery, and Hong Xi Mei Shu Guan. Ten Dynasties of Chinese Ceramics. New York]: [McGraw-Hill], 1993.

Clark, Sharri R. The Social Lives of Figurines: Recontextualizing the Third-millennium-BC Terracotta Figurines from Harappa (Pakistan). Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University; Vol. 86. Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.A.: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology : in Association with the American School of Prehistoric Research, Harvard University, 2016.

Clunas, Craig. Pictures and Visuality in Early Modern China. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1997.

Earle, Joe., Halsey. North, North, Alice, and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Contemporary Clay: Japanese Ceramics for the New Century. Boston, Mass.: MFA Publications, 2005.

He, Knight, Vinograd, Bartholomew, Chan, Knight, Michael, Vinograd, Richard Ellis, Bartholomew, Terese Tse, Chan, Dany, and Asian Art Museum of San Francisco. Power and Glory : Court Arts of China's Ming Dynasty. San Francisco, Calif.]: Asian Art Museum--Chong-Moon Lee Center for Asian Art and Culture, 2008

Honda, Shimazu, Rooney, Shimazu, Noriki, and Rooney, Dawn. The Beauty of Fired Clay: Ceramics from Burma, Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand. Kuala Lumpur ; New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Hutt, Michael, and David N. Gellner. Nepal: A Guide to the Art and Architecture of the Kathmandu Valley. First ed. Boston: Shambhala, 1995.

Lurie, Samuel J., Beatrice L. Chang, and Geoff. Spear. Fired with Passion: Contemporary Japanese Ceramics. First ed. New York: Eagle Art Pub., 2006.

Mookerjee, Ajit. Ritual Art of India. London: Thames and Hudson, 1985.

Murck, Alfreda. Poetry and Painting in Song China : The Subtle Art of Dissent. Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center for the Harvard-Yenching Institute, 2000.

Murphy, Stephen A. Cities and Kings: Ancient Treasures from Myanmar. Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, 2016.

Pal, Huyler, Cort, Luczanits, Banerji, Pal, Pratapaditya, Huyler, Stephen P., Cort, John E., Luczanits, Christian, Banerji, Debashish, and Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Host Institution. Puja and Piety: Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist Art from the Indian Subcontinent. Santa Barbara, California: Santa Barbara Museum of Art in Association with University of California Press, 2016.

Pal, Pratapaditya., Valrae. Reynolds, and American Federation of Arts. Art of the Himalayas: Treasures of Nepal and Tibet. First ed. New York: Hudson Hills Press in Association with the American Federation of Arts, 1991.

Richards, Glen, and Glen, Clayton. South-east Asian Ceramics : Thai, Vietnamese, and Khmer: From the Collection of the Art Gallery of South Australia. Asia Collection. Kuala Lumpur ; New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Rawson, Philip S. The Art of Southeast Asia ; Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, Burma, Java, Bali. Praeger World of Art Series. New York: F. A. Praeger, 1967.

Saint-Gilles, Amaury. Earth'n'fire : A Survey Guide to Contemporary Japanese Ceramics. Tokyo: Shufunotomo, 1978.

Sakya, Jnan Bahadur. Short Description of Gods, Goddesses, and Ritual Objects of Buddhism and Hinduism in Nepal. Fifth ed. Kathmandu, Nepal: Handicraft Association of Nepal, 1996.

Truong, Philippe., John. Stevenson, and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The Elephant and the Lotus : Vietnamese Ceramics in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. First ed. Boston, Mass.: MFA Pub., 2007.Thailand

Watt, James C. Y., Maxwell K. Hearn, and Metropolitan Museum of Art. The World of Khubilai Khan : Chinese Art in the Yuan Dynasty. New York : New Haven [Conn.]: Metropolitan Museum of Art ; Yale University Press, 2010.

Welch, Matthew, Sharen. Chappell, and Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Netsuke: The Japanese Art of Miniature Carving. Minneapolis, Minn.: Paragon Pub. : Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 1999.

Publications by the Lowe

Hands & Earth: Six Perspectives on Japanese Contemporary Ceramics

China’s Last Empire: The Art and Culture of the Qing Dynasty, 1644-1911

Introspection and Awakening: Japanese Art of the Edo and Meiji Periods, 1615-1868

From The Vault, Building A Legacy: Sixty Years of Collecting at the Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami

Articles

Jongeward, David. "Imagining Buddha: Along the Fabled Silk Road Lay Gandhara, an Ancient Region That Played a Central Role in One of Asian Art History's Most Extraordinary Developments." Rotunda 33, no. 2 (2000): 16.

Nylan, Michael. "Style, Patronage, and Confucian Ideals in Han Dynasty Art: Problems in Interpretation." Early China 18 (1993): 227-47.